2019 © All elements contained on this website and in particular texts, illustrations, sounds, images and videos fixed or animated reproduced on this site as well as the marks and logos present on the site are protected by the right of the intellectual property, and this in the whole world. Any use or reproduction total or partial of the site or its elements is strictly prohibited.

Bargny The real face of economic emergence

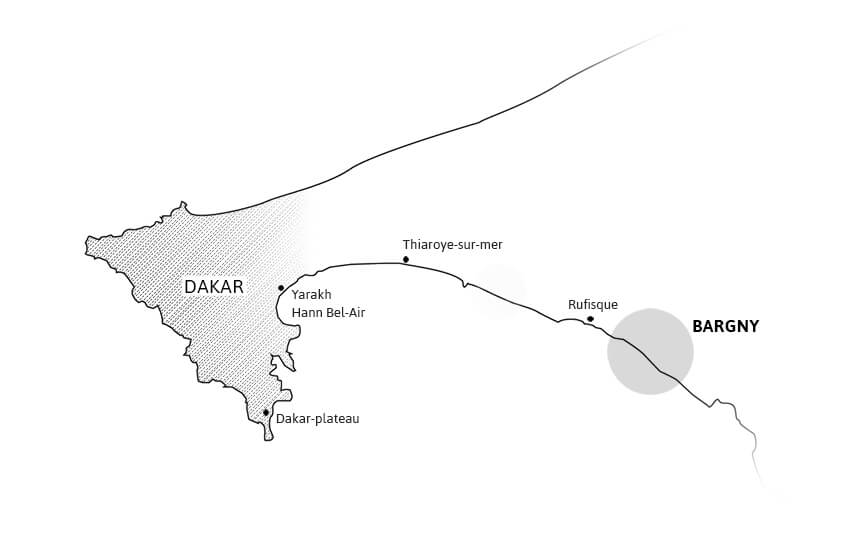

2014. Macky Sall, president of the Republic of Senegal, approves a new development model to speed up the country’s emergence. “Ambitious” and “futuristic”, the Emerging Senegal Plan (ESP) promises to modernise all of Senegal by 2035. It’s an attractive promise, but not without consequences. Bargny, a small community in the suburbs of Dakar, is central to this programme.

On a Tata bus, the wind sweeps across people's faces along the sliding windows that are difficult to open. After standing cramped together for three hours in 40 °C heat, the settlement of Bargny appears before us in a cloud of dust.

Bargny, a village of Lebu origin (Senegalese communities concentrated on the Cape Verde peninsula, traditionally composed of farmers and fishermen), with 70,000 inhabitants, is the planned site of a new industrial suburb of the Senegalese capital. For decades, the area’s residents have seen their land confiscated and their resources depleted. A series of major projects have jeopardised their local economy and social organisation: the construction of a cement factory in 1984; the construction of a coal plant, which residents have been fighting since 2008; and an urban development hub aimed at Dakar’s upper class and foreign investors, which has been under construction since 2014. All this comes in addition to a decade of continuing coastal erosion and the announced construction of a new mineral and bulk port a few months ago. The community is under attack from all sides.

Relocations. Expulsions. The arrival of the plant, the port and the urban development hub has driven a wedge between the community’s inhabitants. Both proponents and detractors agree on the damage that these projects will cause to the environment and to the local economy, but due to precarious economic conditions, some support the projects in hopes of finding employment.

Cheikh Fadel WadeWe are talking about economic emergence, but this emergence has to be general, not sector-specific.»

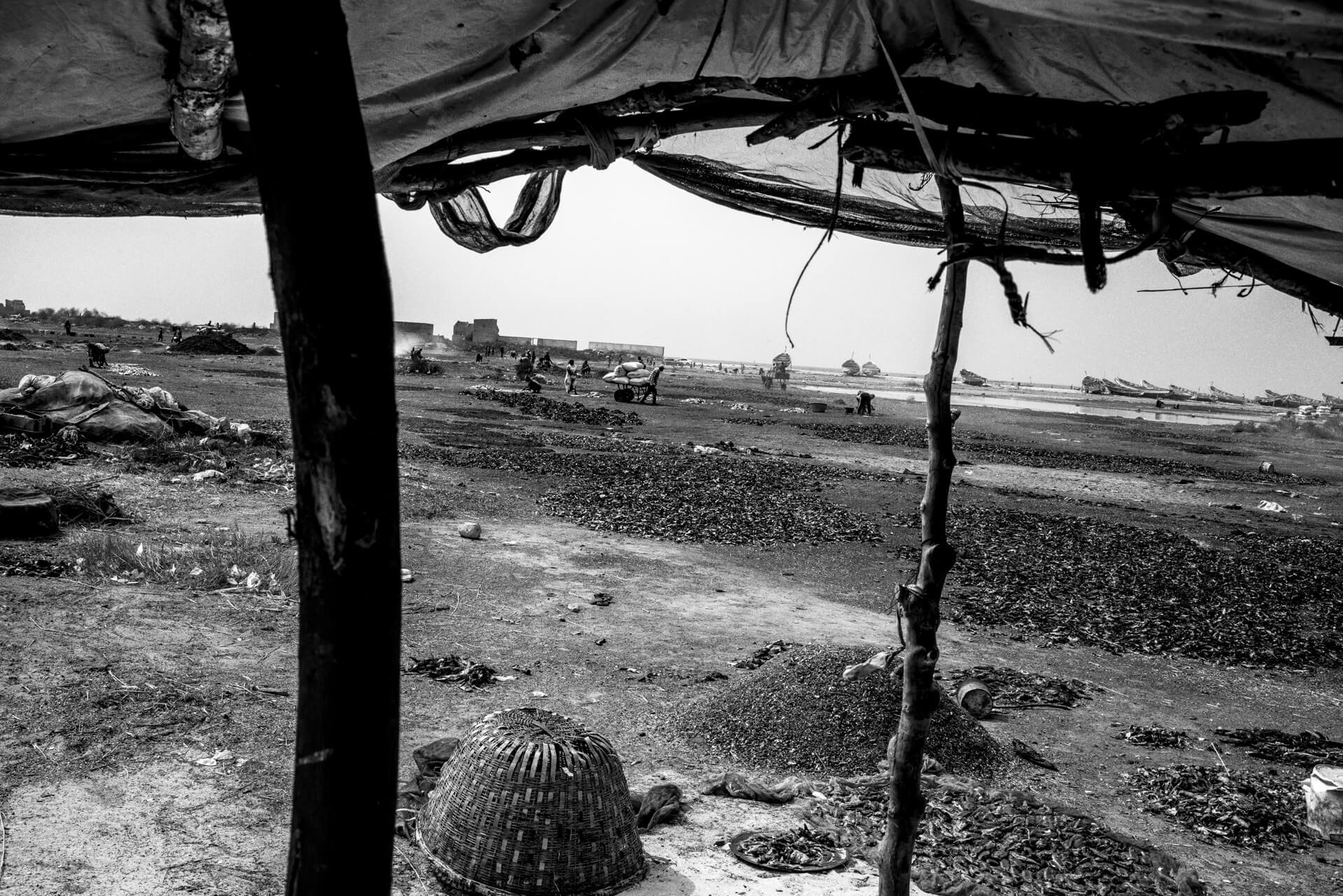

In Bargny, like many Lebu communities, fishing represents 70 % to 80 % of the local economy. It’s a key sector of the country’s domestic economy. Men, women, children, adults and pensioners depend on these activities for their household incomes. Fishing and agriculture are more than just economic activities: they form the basis of social organisation and solidarity. Daouda, a former engineer for Industries chimiques du Sénégal (ICS) and native of Bargny, is worried. He wonders how such projects can be justified when they threaten thousands of jobs.

Cheikh Fadel WadeWe are talking about economic emergence, but this emergence has to be general, not sector-specific.»

“When a person is ill, the community will sometimes fish for him for a day to cover the costs. We call it a non-working day. The canoe and the thirty people on board come back with 3 million CFA francs (€4,500) worth of fish that are given to him. But if we move towards a modern system that impoverishes people and their relations, inequality will grow. It’s a danger for all population groups”.

While the Senegalese state is busy establishing its country as an essential crossroads of West Africa by investing in major territorial redevelopment projects and the extension of the autonomous port of Dakar, it is simultaneously depriving its people of their most important source of revenue and their land by means of “public utility” decrees. Already confronted with years of coastal erosion, which destroys homes along the Atlantic coast every day, inhabitants have been offered no solutions to help them face the advancing sea.

South

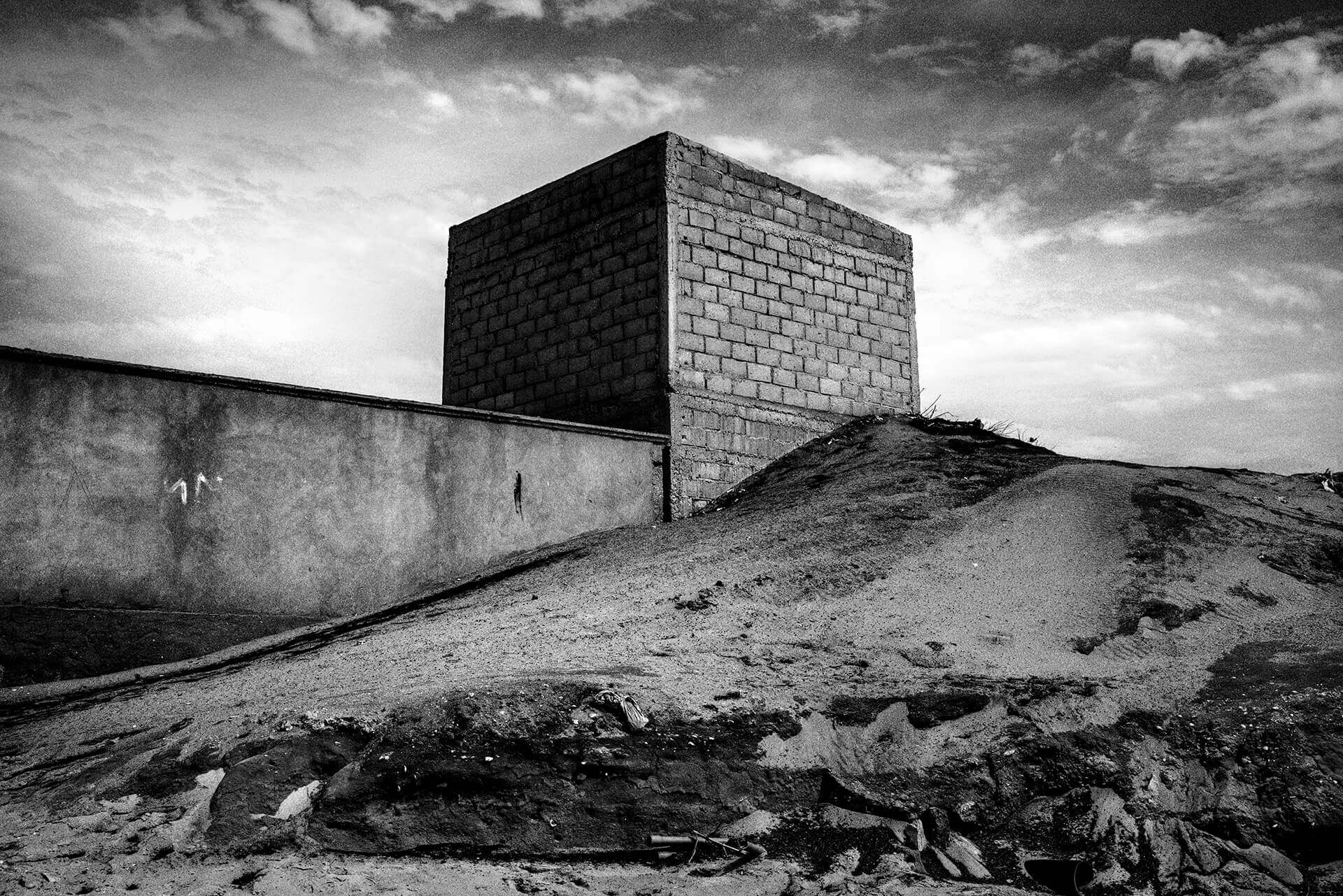

Fatou Samba, a woman who processes fish products at the Khelcom site, sits on her couch in the sweltering heat of a small space that functions as living room. Her fan blows at maximum power. A victim of coastal erosion like so many other inhabitants, one of her rooms was washed away by the sea earlier this year. The entrance of her house had to be moved. “We’ve just installed the door on the side facing the alleyway. It used to face the beach”. Family compounds here are exposed for all to see, the once private now increasingly public.

Bargny has suffered immense damage along the Atlantic coastline since the 1980s. But as the coastline has receded several dozen metres, the situation has recently become increasingly intense. “I can say that I live right on the water because it literally enters my house. Less than twenty years ago, there was a wide beach between the compound and the sea”, Fatou says.

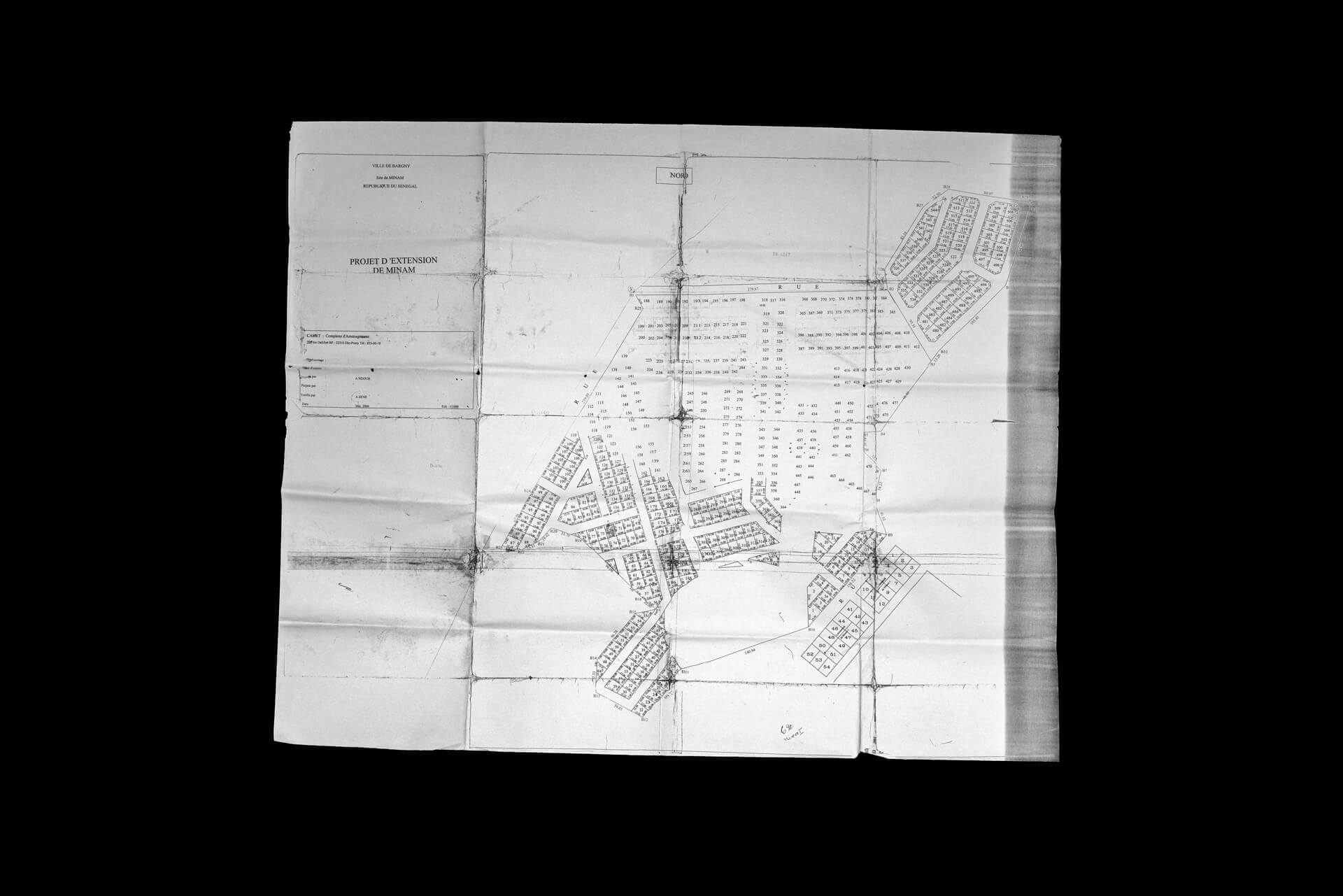

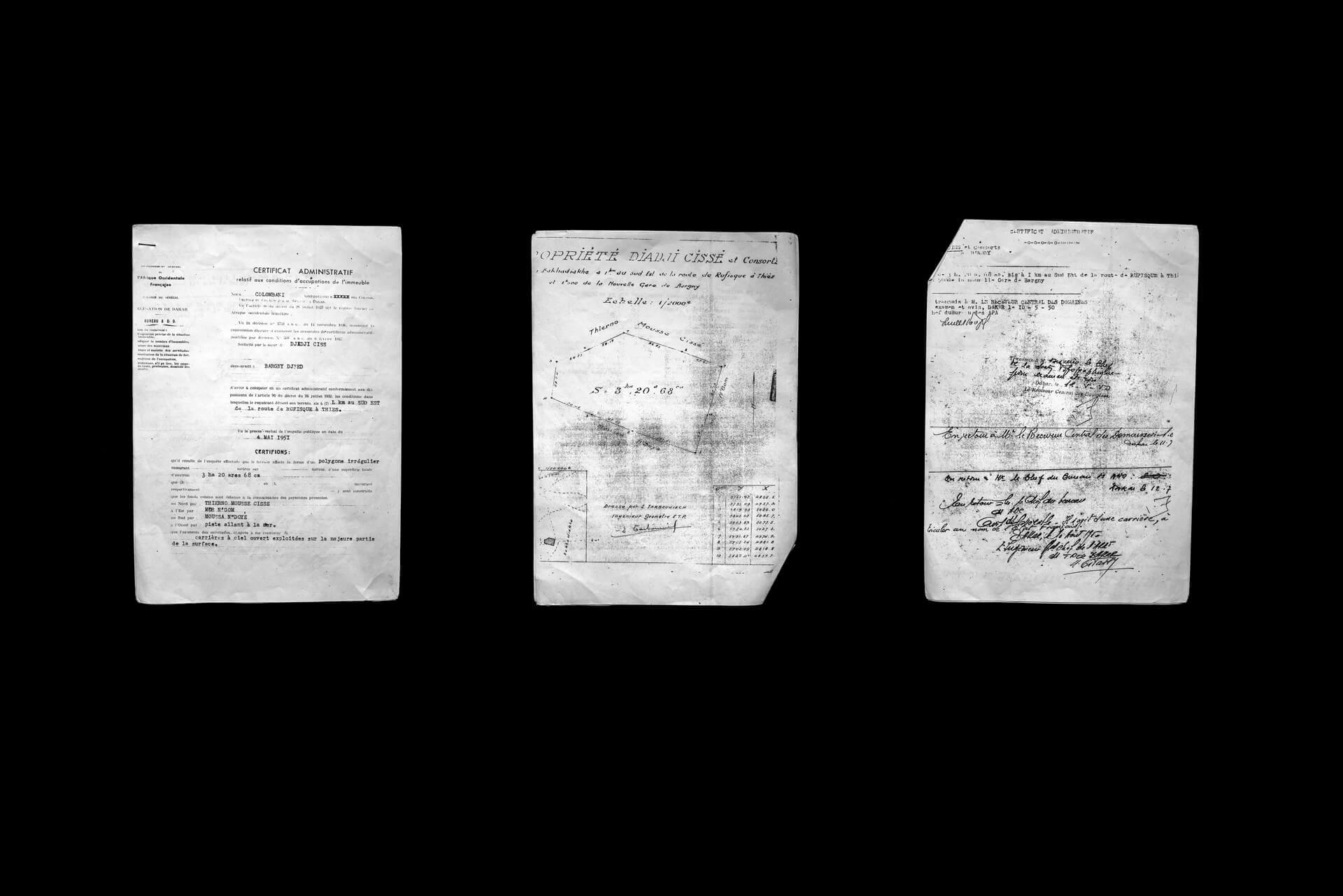

In 1995, the sea began to erode Miniam, a district in the west of Bargny. The prefecture of Rufisque (the department to which Bargny belongs) responded by implementing a project to expand the village (Miniam I) in order to relocate the victims of coastal erosion. In April 2006, the neighbourhood saw a second expansion, Miniam II, which received positive feedback and was confirmed by an agreement between the owners, the mayor and the prefect of Rufisque. A total of 1,433 plots were assigned to the victims of coastal erosion. Most of them went to Rufisque to pay the delimitation costs for their respective sites (varying from 30,000 CFA francs [€45] to 45,000 CFA-francs [€70]) to the treasury. Two years later, Abdoulaye Wade (President of the Republic of Senegal from 2000 until 2012) proclaimed the area of “public utility” in order to build a coal plant. He sold the land (where both Miniam sites were located) for the modest sum of 1,450,000,000 CFA francs (€2,210,509) to a Swedish project developer, Nycomb Synergetics Development AB. Hundreds of families had to be moved from the two locations. “They never even got to build their houses. Their incomes were too low and they lacked the resources to build fast enough. Maybe if they had the plant would never have been built here”, says Assan, a former fisherman and president of the local fishing committee.

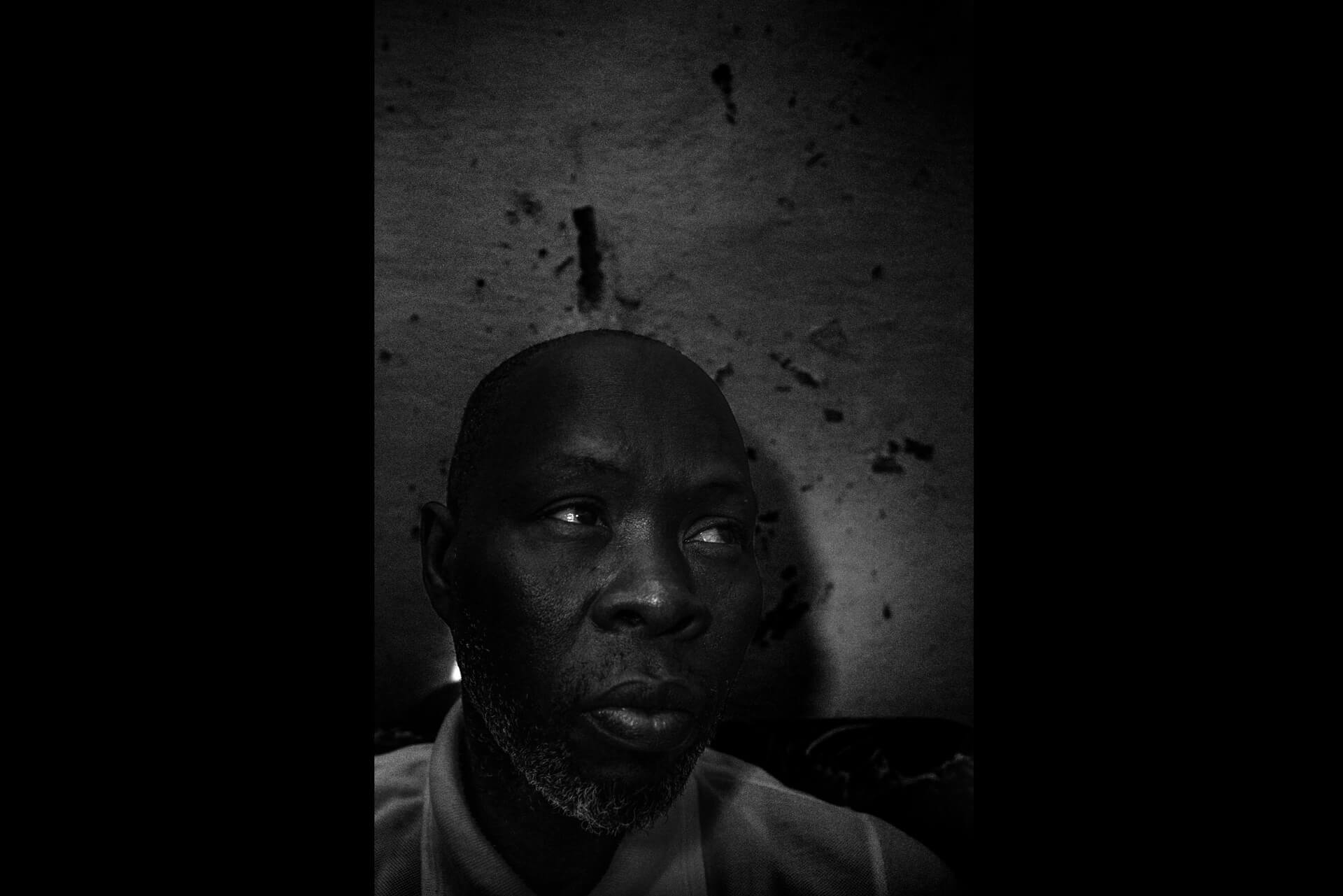

Owners saw their land taken away without having any say in the matter. They received only partial compensation or no compensation at all. Cheikh is one of the heirs of the parcels where the power plant now stands. He saved for more than thirty years to build his house, now located 500 meters from the plant. “I served for 32 years on the police force. I built my home and now there’s a power plant right next to it, a plant that will pollute Bargny. It’s a disaster. I’m 63, I was born and raised in Bargny”. He adds, “We never received anything from the government”. Until now, no solution has been found for relocating the former residents of Miniam I and Miniam II.

Fatou SambaThis coastal erosion is responsible for the destruction of our village.»

East

The community’s schools, homes, fish processing sites, ranches and farms now have a new neighbour: the Sendou I coal plant. Inhabitants condemn the breaching of article L13 of the environmental code, which states that every “category 1” installation must be located at least 500 metres from homes, public institutions, streams, etc. Sendou I is only 231 m away from the closest homes and 388 m from the primary school of Miniam.

Although an environmental and social impact study was carried out, it neither took into account the community’s water supply (the project requires 15,000 m³ of water an hour, or 4 million m³ per year) connected to the local pipelines, nor the extreme pollution produced by the combined emissions of the coal plant and the Sococim cement factory (to the west of the community), which already has a 24-megawatt plant. “The plant is a real danger. And it also requires a lot of fresh water. Currently, the Senegal Water Development Corporation (SDE) doesn’t even have the capacity to provide the needed supply of water to Bargny. At the time of testing, the area suffered a weeklong water shortage. It’s a public health issue”, says Daouda, a member of one of the several affected communities. Testing continues to cause shortages.

Research on the impact of transporting coal from the autonomous port of Dakar (35 km) is also lacking. 386,000 tons of coal are transported annually, requiring 287 lorry trips a day over a span of five days, nine times a year. The space for joint management for the re-introduction of the fish population close to the plant hasn’t been taken into consideration either. Artificial reefs were created, which were financed by the World Bank. The project also makes no mention of this space for joint management, which will require a cooling system to be installed in the same area. “If we dump water in the sea, I’m scared it will also contain toxic waste”, Assan says. For Cheikh, the absurdity has reached its peak: “How is it possible for the World Bank to finance both the development of Bargny and another project that destroys it?” This calls into question the consistency of the projects and the country and region’s vision for global development, especially with the new urban hub being built only ten kilometres away.

Daouda GueyeThe coal plant will release a million tons of CO2 per year.»

While coal currently makes up about 40 % of the world’s electricity production, its use is increasing and it is expected to surpass oil in 2020. A 2016 Oxford University study highlights the impossibility of limiting global warming to 2 °C if these types of plants continue to be built. The out-dated, backward-looking and inappropriate nature of the project isn’t questioned by the authorities, investors and developers.

In a letter dated 16 November 2017, the Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO), one of the project’s backers, confirms that it has had a zero-carbon policy in place since 2015, but cannot withdraw investments that have already been made in the Sendou I plant project. And although FMO admits “that during the verification period in 2009, several essential environmental and social (E&S) aspects [...] should have been looked at in greater detail and [that] the contextual risk should have been better analysed”, it only promises that “the lessons of this project and other projects will be integrated into its policy in order to improve the assessment of E&S risks”. To receive support from the community to build the power plant, the project company, Compagnie d’électricité du Sénégal SA (CES), founded by Nycomb, promised, through a “build, own, manage” agreement valid for 25 years, to rebuild a mosque, plant trees, deliver school utilities, contribute to religious pilgrimages, distribute “Ramadan food baskets” and donate cement.

It seems like nothing can prevent the construction of Sendou I, which will be quickly followed by the mineral and bulk carrier port. This port will eventually transport coal from the power plant as well as store the many oil products and minerals of industries in the regions, such as those of the Sococim cement factory.

West

Upon entering Bargny, Sococim, a subsidiary company of the French Vicat group and one of the largest cement factories in West Africa, towers over the landscape thanks to its sheer size and dust cloud emissions. Close by, a farmer does his best to maintain his field despite the cement dust that settles everywhere. “My grandfather had a farm here. The dust is destroying us. If you go to the sea, it’s no different. The wind blows dust in your eyes and ends up on the ocean floor.” Babacar, a fisherman, agrees. “If you dive under the water you see that the sea floor has become a piece of cement. The fish that eat from it can’t survive anymore.”

Cissé, a teacher, lives in a building not far from the Sococim quarry further to Bargny’s north. Twice a week, on Wednesdays and Fridays, mine detonations for the extraction of limestone from the quarry shake the walls of the building. Since the company was founded in 1948, its environmental and social impact has only continued to grow. Production has increased from 40,000 tons to 3.5 million tons a year. Mine explosions from the quarry damage the walls of homes and structures in the area. According to Cissé, the cement factory is largely responsible for the respiratory problems that affect local residents, which could be linked to pollution and dust that result from the factory’s activities. According to the Global Carbon Project, an international organisation responsible for measuring and understanding carbon dioxide-cycles in the atmosphere, cement production is the highest CO2 emitting industry after coal, oil and gas.

Sococim provides the local school with Bic pens and notebooks and donates cement to help the victims of mine explosions rebuild roofs and walls that are cracked or collapsed, and can thus claim to be “an important player in socially conscious industry in Senegal”. This type of commitment is common in the region.

Sococim occupies 462 hectares of agricultural land, from which it expelled countless farmers. Recently, the company started to expand its quarries into an area that has been zoned as residential. Confronted with this “giant”, residents were forced to accept compensation according to the value of their houses, not to the value of their land.

North

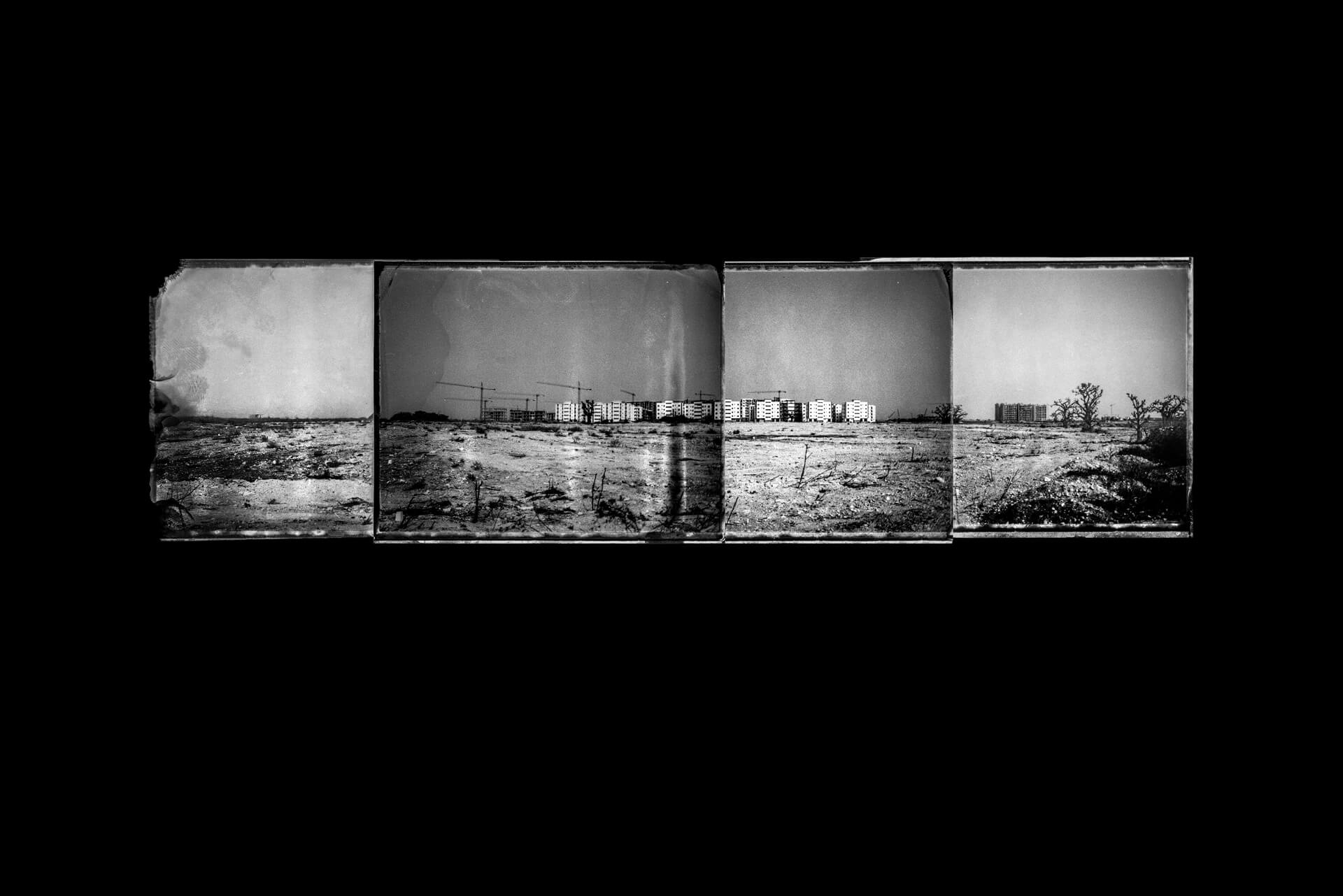

Less than 5 kilometres from the quarries, construction on the Diamniadio urban hub, which spans four municipalities, is well underway. If you make your way through the fields and tall grass, you can even get there by foot. It comprises an area of 1,644 hectares, 70 % of Bargny’s farmland of mostly okra crops. Construction started in May 2014, two years after the election of Macky Sall.

In his official statement about the urban hub, a cornerstone of the Senegal Plan, Macky Sall presents himself as an innovative president and symbolic figure who “dreamt of a new city, open to the world”, which he “designed and implemented”. His goal: to relieve the capital city and revitalise the national economy by attracting private investors from the diaspora or abroad through free allocation of land, presented as “unexploited”, to stimulate growth, generate employment and make Senegal an important player in international competition. Halfway between Dakar and the new Blaise Diagne International Airport (AIBD), a toll highway (built by the French Eiffage group) and an electric train that connects Dakar and Diamniadio (a collaboration between Eiffage, SNCF and RATP), Diamniadio is slated to become the centre of a new model capital city, initiated by “his excellency Macky Sall”.

Residential neighbourhoods, a ministerial city, sport complexes, art museums and exhibition space, a university, opera, hotels and luxury boutiques are the “promise of a new Senegal”, “opening up to modernity”, but “rooted in its traditional values”. A “sustainable modernisation” with the goal of combatting the poverty that affects more than 47 % (57 % in rural areas) of the population. And even though “social” housing is part of the project, units cost around 15 million CFA francs (€22,867), while the average daily wage is around 1,500 (€2.30) to 3,000 CFA-francs (€4.50).

Sold through promotional videos as a project with “ultramodern” architectural ambitions, not without references to Dubai (UAE), the urban hub is already home to a Radisson Hotel and the Abdou Diouf conference centre. The ministerial city and a few buildings in vernacular architectural style are currently under construction.

Daouda GueyeFor the sake of development they are making people poorer. We can’t call this economic emergence.»

Only a few kilometres from the urban hub of Diamniadio, near the coal plant, a mineral and bulk carrier port is being built. The Senegal Minergy Port company, an official Senegalese special purpose vehicle was set up to design, build and operate the port. Construction began in November 2017. For a price of 290 billion CFA francs (€44 million), the new port will feature a four-kilometre long pier and a 484-hectare area, including two terminals for liquid bulk (hydrocarbons, petroleum, liquid natural gas, chemicals and food) and dry bulk (iron ore, bauxite, alumina, etc.) and an industrial zone with a capacity of 12 million tons of bulk goods per year. This future maritime hub of West Africa is not without danger for Bargny, a community largely dependent on fishing. Again, “no single environmental impact study has been carried out”, says Daouda, while “the bulk carrier port will take all the chemicals from the port of Dakar transfer them to Bargny.”

Despite the promise to create 740 to 2,600 jobs – an important issue in a country where unemployment is around 30 % and the informal sector comprises around half of GDP – people are still worried. “Bargny is a fishing village, so if you don’t have the required qualification or documentation, you can’t work for just any company. Even if the companies come, they won’t employ us if we don’t have the skills”, says Cheikh. And even with the potential of employment for unskilled labour, “agriculture is still more profitable than a job in a factory”, says Saliou, an employee at the plant construction site. According to Fatou Samba, even though the inhabitants are not “economically comfortable”, they are free from want. “We don’t have nice homes, but we live well. It’s not misery. With fishing, you can make up to 20,000 CFA francs a day (€30.50). Sometimes you don’t earn anything. Sometimes you make just enough money to pay back what you’ve borrowed. But at least we’re self-sufficient.”

In the process of becoming a new industrial suburb, Bargny is in danger of facing the same problems as many Lebu communities in the region (such as Yarakh/Hann Bel-Air or Thiaroye-sur-Mer): speculation, pollution and depletion of natural resources. Historically owners of family compounds passed from generation to generation, inhabitants of Bargny are gradually being forced to rent, made dependent on industries that settle in the region, and deprived of all resources.

“To his excellency Macky Sall, president of the republic, regarding the pollution, the coastal erosion, the urban hub Diamniadio, the loss of land, the disappearance of agriculture and the loss of employment: the grandeur of a nation isn’t measured by its beautiful roads and infrastructure, but by its capacity to deal with the issues affecting its most vulnerable social groups.”

From a memorandum by the Saama Lignou Moom collective

Credits

- Director : Laurence Grun - Pierre Vanneste

- Image - Photography : Pierre Vanneste

- Copywriter : Laurence Grun

- Music : Eric Desjeux

- Editing : Antoine Castro

- Sound Mixing : Enzo Tibi

- Maps Designer : Kevin Lerens - Bruno Tellier

- Web Developer : Pierre Lovenfosse

- Web Developer : Tim Mercier

- Translator (en) : Brandon Jay Johnson – Younes Rifaad

- Reviser & Corrector (fr) : Alain Le Saux – Marinette Mormont

- Reviser & Corrector (en) : Brandon Jay Johnson

- Fixer : Cheikh Fadel Wade

- Production : Nuit Noire production

In partnership with

A webdocumentary produced with the support of